I recently attended an European chapter of ASIS&T Information Science Trends online conference This year it focussed on health information hehaviour. The following are my digitally-assisted memories of #AECIST20, i.e. adaptations of my live-tweets from the event. As ever, this report is mostly to help me sort what I need to do from what I want to do after being stimulated by many fascinating presentations. Any mistakes or misrepresentations in the below are of course my mistakes.

Where possible, peoples’ names are hyperlinks to Twitter profiles or ORCID records, and presentation-titles are links to their abstracts on Zenodo. Click any images to see the full-size versions. My asides, made during the conference and as I wrote this piece are in green italics. Sheila Webber has also blogged about the event: Monday part 1; Monday part 2; Tuesday; Wednesday part 1; Wednesday part 2.

Contents

- 8 May

- Introduction

- Health literacy in practice in Ireland

- Taking health information behaviour into account in user-centered design of e-health services – key findings from an ongoing research project

- Girls’ Positions and Authoritative Information Sources in Finnish Online Discourses on the HPV Vaccine

- Teaching Online Health Literacy at the University Level (poster)

- Information avoidance and diabetes: a preliminary empirical study (poster)

- 9 May

- Health (mis)information behaviour in the Covid-19 era

- Usage of social media in finding information related COVID-19

- Correcting health misinformation online: Collaborative crosschecking

- How can the Government tackle an Infodemic during a Pandemic? (poster)

- #COVID-19 Misinformation: Saudi Arabia as a Use Case (poster)

- 10 May

Monday 8 May

Introduction

We were welcomed to this online-only conference by Aylin Ilhan. This was followed by a full introduction to the event by Clara M Chu. She spoke about some horrific experiences, and stated that ‘healing begins with the truth’. This thread was very relevant to some discussion in one of ‘my’ Edinburgh community councils about renaming or giving information about Edinburgh streets named after horrible things or people. She challenged researchers to consider alternative sources of data, alternative and challenging topics, and asked whether we as researchers can help to uncover truth and help healing? She said that we were about to hear an example of supportive research, so I was on the edge of my home-office seat. Thanks to Bebe S Chang for grabbing Clara’s slide:

Inez Bailey: Health literacy in practice in Ireland

Inez is the chief executive of the National Adult Literacy Agency in Ireland. She began by asking ‘what is literacy?’ Part of her answer is ‘it’s a social practice’:

Someone tweeted that she loved how NALA starts from the perspective that beginner readers are not beginner thinkers.

Someone tweeted that she loved how NALA starts from the perspective that beginner readers are not beginner thinkers.

Inez then noted that health literacy and numeracy rely on mutual understanding. Here is Inez’ definition of health numeracy:

|

|

Inez next delved into data from a 2013 OECD survey of adult skills , asking the audience to predict some answers:

|

|

One of the questions in the survey looked at whether people can understand food-labels. This skill is ultra important to me because I’m a vegan who has Type 1 diabetes.  There was also an EU Health Literacy survey in 8 countries. It found that 10·3% of respondents had ‘inadequate’ health literacy and 29·7 had ‘problematic’ health literacy. Here are Inez’ reasons why that is so important and frightening! The slides about the Irish findings really chimed with some things I have learnt about some people with diabetes.

There was also an EU Health Literacy survey in 8 countries. It found that 10·3% of respondents had ‘inadequate’ health literacy and 29·7 had ‘problematic’ health literacy. Here are Inez’ reasons why that is so important and frightening! The slides about the Irish findings really chimed with some things I have learnt about some people with diabetes.

|

|

|

|

Based on such findings, NALA has been lobbying with some success, in that Ireland’s health service executive is taking on relevant objectives.

So Inez then looked at ‘Delivering a health-literacy friendly service’. Part of the way to do that is for healthcare professionals to audit themselves, to find and then address issues. Another part is development of literacy-friendly quality standards.

So Inez then looked at ‘Delivering a health-literacy friendly service’. Part of the way to do that is for healthcare professionals to audit themselves, to find and then address issues. Another part is development of literacy-friendly quality standards.

|

|

Inez then delved into how we can communicate more effectively. Part of this is using simpler words and better presentation of words and numbers, including on food-labels. I have a deep and personal loathing of Times New Roman and lack of leading (vertical space between lines of text). The final point on the the ‘plain numbers’ slide is – or should be – standard publishing practice anyway!

|

|

|

|

|

|

Inez noted some useful resources, and the importance of checking that people have understood what has been said. She concluded that health literacy is a lifelong essential, needing a range of responses, but leading to better (health) services.

|

|

|

|

Questions

- If literacy is a social practice, how could it be measured/understood by us researchers with regard to the ‘social’ effect?’

- Research at Lancaster University is very relevant. ‘New literacy studies’ is the relevant search-term.

- Someone noted that much of Inez’s presentation was all about quantitative data, and suggested that literacy as a social practice can’t/shouldn’t be ‘measured’. If we can’t at least assess how well a person is or people are doing, we can’t know whether measures to support them are effective. Having said that, I know – from trying to do so – that measuring workplace information literacy can be very difficult!)

- Someone else commented that there are information literacy researchers who position it as a social practice. Yes! We do not learn to read and understand all by ourselves. What we learn and understand – and what things actually mean – is mediated by all sorts of social circumstances and practices. But if you don’t know whether your class of primary pupils is learning to read better, you don’t know whether you are teaching effectively, other factors aside. And if you don’t know whether using this font is more effective than that font on a food-label, you have no way of making informed decisions.

- Research at Lancaster University is very relevant. ‘New literacy studies’ is the relevant search-term.

- There was discussion of whether literacy can be lost.

- Inez said that many people in Ireland taught Irish in school, but then lose these skills due to lack of practice. In general, as we get older, we lose some abilities. That squares with my personal experiences!

- Someone tweeted ‘I wish the recognition that people don’t ‘keep’ levels of literacy – it is practised and is a practice – was more prevalent in #infolit research. That seems fair enough to me.

- Inez said that many people in Ireland taught Irish in school, but then lose these skills due to lack of practice. In general, as we get older, we lose some abilities. That squares with my personal experiences!

- Why are especially young adults (15-34) are least likely to ask for more information? Are they afraid of not getting a helpful answer again or what is the main problem here?’ This is very relevant to my research with Gemma Webster, so I was keen to hear Inez’ answer.

- Inez used ‘smoking cessation’ as an example. My alter-ego shouted ‘no chance of that here!’ Inez suggested embarrassment might be part of the answer. She emphasised the importance of practitioners giving people encouragement to ask questions using the ‘ask 3’ idea. She said that some people try to hide that they don’t understand health information, so became aggressive to practitioners

- Where should we start to be more proactive, who is responsible?

- ‘if education worked, we wouldn’t need this’ is a myth. Literacy is a muscle – it needs exercise. How does this fit with mine and Peter Cruickshank‘s community council IL findings?

- Someone commented ‘One of my favourite literacy articles talks about how hard it is to read an aspirin bottle – all the tacit social and cultural implications that are embedded within a label and make it so complex (Gee, 1988, “Discourse systems and aspirin bottles”)

- ‘if education worked, we wouldn’t need this’ is a myth. Literacy is a muscle – it needs exercise. How does this fit with mine and Peter Cruickshank‘s community council IL findings?

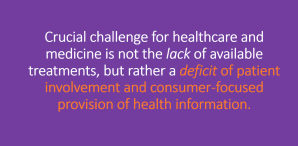

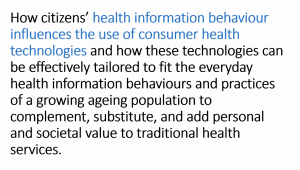

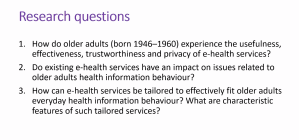

Heidi Enwald; Kristina Eriksson-Backa; Noora Hirvonen; Isto Huvila: Taking health information behaviour into account in user-centered design of e-health services – key findings from an ongoing research project

The presentation was given by Heidi Enwald. Here is the research-team, and a note that this research has a social aim, and research questions:

|

|

|

|

Here are the team’s data sources, and some reading I definitely need to do! Heidi talked about ability to access, evaluate, understand and use health-related information.

|

|

|

|

The empirical work consisted of a large population-based survey and focus-group interviews. The researchers blog on their university’s system. Heidi set me even more homework!

|

|

About ‘My Kanta‘: ‘In My Kanta Pages you can see your own health records and prescriptions, request a prescription renewal and save your living will and organ donation testament.’ This reminds me of ‘MyDiabetesMyWay‘.

Questions

- Have you checked older adults’s view of the app?

- There is some work on this.

- Thank you this is an area I’m very interested in – have you looked at digital use in relation to other sources e.g. people, informal networks, other media?

- Sorry I’m having personal/cognitive difficulties in tweeting responses to questions. I’m perhaps too old and slow.

- Do people generally still work all through the ‘old’ age group?

- The research subjects are OK-ish with tech, but ‘the oldest old’ are less so.

- Isto Huvilla added ‘Yes. Sort of, and at least less pessimistic about their ability and likelihood to start using tech than the elderly who are more inclined to think that tech is really difficult. Older adulthood is a transitory period but not only in a negative sense e.g. http://istohuvila.se/node/560

Noora Hirvonen: Girls’ Positions and Authoritative Information Sources in Finnish Online Discourses on the HPV Vaccine

We were asked not to tweet the content of this talk. But as someone else noted, there was an engaging discussion on the impact of cognitive authorities on the decision to vaccinate.

Kristin Hocevar and Melissa Anderson: Teaching Online Health Literacy at the University Level (poster)

Kristin and Melissa noted that they are doing a practical project: all undergraduates can benefit from developing health information literacy. But there is a paucity of relevant literature on teaching HIL to undergraduates.

Kristin and Melissa collaborate as a teacher and a librarian. The curriculum they teach has these elements: ‘learning about eHealth’, ‘cognitive processing theories’, ‘calculating risk’, ‘take part in library-led IL sessions’, ‘a project searching for online health information’.

Questions

- Why was health information literacy not included until now in curricula?

- Pressure from ‘so many other things’. We would like to hear about what happens worldwide, and in other US states.

- What is the difference between health literacy and health information literacy, the focus of this study?

- HL is broader; HIL is interaction with/use of information.

- Should HIL research be qualitative as well as qualitative?

- We need to do both because both have value.

Gemma Webster and Bruce M. Ryan: Information avoidance and diabetes: a preliminary empirical study (poster)

Tuesday 9 May

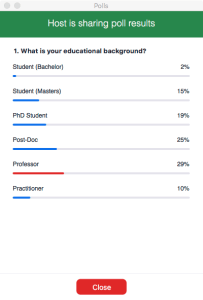

Aylin Ilhan introduced the ASIS&T European chapter folk, and did some audience-research.

|

My answer was ‘other’, meaning ‘none of the above!’ My answer was ‘other’, meaning ‘none of the above!’ |

|

|

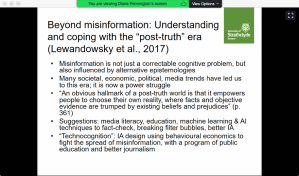

Diane Pennington: Health (mis)information behaviour in the Covid-19 era

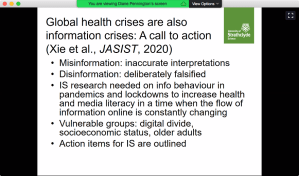

Diane started by noting that her thinking is evolving. When she agreed to give this keynote, we had ‘only’ coronavirus to deal with. Now we have civil rights issues coming to the fore. She asked ‘what steps can you take to make sure information is correct?’, and stated that misinformation is a core problem. She mentioned lies by a certain ‘world-misleader‘. NB ‘world-misleader‘ is my term, and was not said by Diane – she described this person in factual terms only. Meanwhile here is some data on coronavirus, and a classification of types of misinformation. (She also mentioned the digital divide.) Diane’s point here is that global crises are also information crises.

|

|

|

|

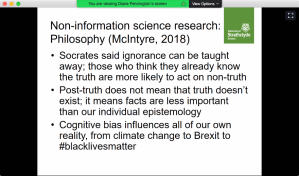

So there are some questions to consider. These are as-yet unrefined precursors to actual research questions. (Diane also noted that mask-wearing is common in China.) So an important question is ‘Who or what do we trust?’ This is reminiscent of the poll earlier. She also talked about ‘cognitive authority’ – her example was male doctors talking about endometriosis, a condition which they cannot personally experience. She stated that coronavirus is within the ‘post-truth’ era. I hate that term and everything it stands for. She then looked at some philosophical precedents.

|

|

|

|

Diane talked more about psychology, and why followers of a certain ‘world-misleader‘ (again, my term) might ignore ‘facts’ about certain coronavirus ‘cures’. There is a power-struggle over cognition in the coronavirus context.

|

|

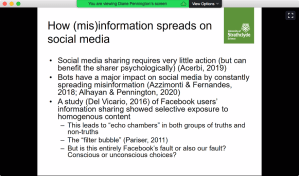

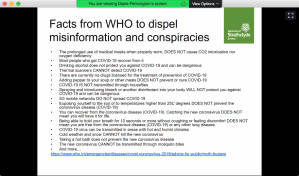

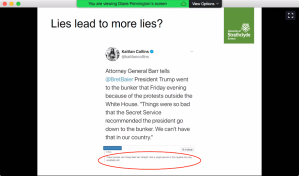

Diane mentioned a personal experience of being in a filter-bubble. I think everyone needs to know your enemy. (That’s my obligatory Manics reference for today.)‘ Diane talked about how misinformation spreads, including desire for ‘dopamine hits’ from social media hits. She said that we shouldn’t just blame the algorithms underpinning what we see on social media but also our own choices. (I think ‘don’t blame the algos – get to the humans that create them!’) Diane also said we should watch out for sources that claim to debunk misinformation. Does anyone remember the Conservative Campaign HQ fact-check hoo-hah? Diane noted some facts from the World Health Organisation, and asked whether lies lead to more lies. I asked whether we knew that since early childhood. Diane later replied ‘Thats what I thought – at least, my parents taught me that!’

|

|

|

|

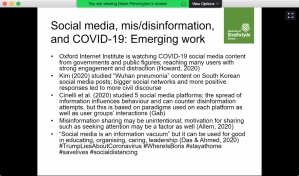

Diane noted some emerging work, and that there is more work to do. This includes sharing some vital information.

|

|

|

|

Questions

- I missed most of this exchange due to a personal phone-call.

- How can we avoid information overload in such research?

- Define your scope and research questions early.

- Aylin Ilhan added ‘Also look to your search keywords.’

- Define your scope and research questions early.

Chat

During the coffee-break, there was an exchange about incorrect use of statistics, and we learnt a new German phrase: Fummeln bis es passt (fiddle till it fits).

Prasadi Kanchana Jayasekara: Usage of social media in finding information related COVID-19

Prasadi‘s presentation wasn’t recorded, so I didn’t tweet about it. But it’s no secret that this presentation was about Sri Lanka, and that this is inflaming my wanderlust. Also, I think that Prasadi did amazingly to get a project done so quickly, especially if it involved getting research funding from scratch. My experience of applying for funding is it can take some time. Of course, it may be simply that I’m not very good at it 😦

Kaitlin Costello: Correcting health misinformation online: Collaborative crosschecking

Kaitlin started by outlining the background to her presentation:

- Patients use online support groups to find and exchange health information with one another

- Healthcare providers and patients are concerned about health misinformation online

- Is health misinformation corrected in online support groups? If so, how?

Some of the above chimes with some of the research Gemma Webster and I are doing. I can’t say how just now.

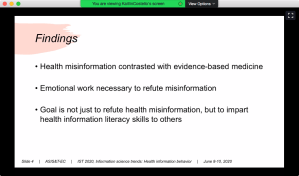

Kaitlin mentioned that that one of her participants hadn’t posted on groups, so she was left with 10 ‘full’ participants. (Again ‘full’ is my term.) Kaitlin’s findings include

- health misinformation contrasted with evidence-based medicine

- emotional work is necessary to refute misinformation

- the goal is not just to refute health misinformation, but to impart health information literacy skills to others,

|

|

|

|

Kaitlin mentioned several types of misinformation, e.g using a sauna instead of going for treatment for a major, fatal condition. (I ask WTF?), or hanging turnips around to help with a certain disease. (I’m not going to say which in case any other people try this.)

Kaitlin gave some examples of collaborative crosschecking, ofevaluation techniques that users shared and of emotion-work. Collaborative crosschecking is where users attempt to teach others how to combat misinformation by sharing their own searching and evaluating skills. NB ‘watch the pages’ (not eh ‘evaluation’ slide means ‘only trust authoritative sources, e.g. ‘.gov’. I want to ask Roger Water’s question ‘Should I trust the government?‘ See later for when I actually did. Another commenter said ‘interesting focus on emotional work in “correcting” people/teaching people more appropriate information skills and ways of engaging with health information’.

Kaitlin then noted some of the implications of this work. For me, the final implication (healthcare providers should also educate patients about evaluating health information) is very reminiscent of yesterday’s keynote.

|

|

|

|

Questions and comments

Someone tweeted ‘Language is again so important! We saw it yesterday during the keynote by Inez Bailey, and we also discussed the language if we would like to tell somebody if the information is not adequate or how to use information.’

- Is this research continuing?

- Not right now but there are many opportunities. I have just finished another related study.

- Is this behaviour just in support groups?

- Tthe more diffuse a group is, the less likely collaborative cross-checking is.

- I wonder if support groups can be considered as communities of practice. If so, is that a research opportunity?

- Tthe more diffuse a group is, the less likely collaborative cross-checking is.

- What are people’s reactions when they are told to verify online information?

- I didn’t look into that, but it would be interesting to see what happens when people are gently corrected. I’d love to know!

- Would there be the risk that someone abuses collaborative cross checking with spreading fake news. Or might the rest of the community rather reveal this behaviour?

- More polarised topics might be more difficult to treat gently. There is Annemaree Lloyd‘s work on information behaviour of refugees.

- What if someone’s response to ‘trust government websites’ is ‘I don’t trust the government’?

- You should look for multiple reputable sources saying the same thing. This will lend credence to whatever the government says. (I hope!)

Chat

I really enjoyed the chat about what we did during the breaks.Others did stretching, cleaning, caffeine and cakes. I did laundry, guzzled diet Irn Bru and of course smoked a lot. In fact I really enjoyed this three online half-days format. All day at a conference can be too taxing, and it’s far too easy for my laptop’s batteries to fail. Have you ever been at a conference with the right amount of powerpoints, enough power-points, and your favourite mug? And how much did we all save, and not cost the environment, by not travelling?

Later chat was on more serious topics: the power of information; the legitimacy of information avoidance; the number of conference participants in privileged statuses (having qualifications, internet access etc); consideration of what is a ‘fact’, and how ‘facts’ are seen by different disciplines and by people of different backgrounds; the contexts, channels and people though which information is shared.

Patrick O’Sullivan and Carolanne Mahony: How can the Government tackle an Infodemic during a Pandemic? (poster)

This was presented by Patrick O’Sullivan. Patrick set the scene by talking about balancing fairness to individuals with while maximising ‘social’/communal benefits in clinical trials. The work in this poster is about applying this balance to government information. The Irish constitution requires freedom of expression (even the freedom to be wrong) but without defaming others, causing harm, etc. It’s a big balancing act!

Patrick noted that in a health crisis, state control rises against individual control. Does this mean we should penalise those who spread misinformation? What about those who truly believe the misinformation they spread is true? Can you say ‘mens rea‘? I liked Patrick’s frequent mentions of ‘justice’.

Patrick noted that in a health crisis, state control rises against individual control. Does this mean we should penalise those who spread misinformation? What about those who truly believe the misinformation they spread is true? Can you say ‘mens rea‘? I liked Patrick’s frequent mentions of ‘justice’.

The next stage of Patrick’s work is to try to apply this framework to reality. He noted that ‘individual’ fake news might become ‘communal’ fake news and even ‘state’ fake news. (I thought ‘AARRGGHH’ and of Commentarii de Bello Gallico.)

Questions

- How might the balance be affected by info litaracy?

- We should probably consider what the individual might actually know thanks to their qualifications etc.

- Should there be/is there another dimension when facing GLOBAL challenges, where many countries are concerned (individual – community – global

- All countries are facing coronavirus. Then there is that world-misleader previously mentioned.

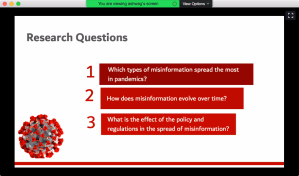

Ashwag Alasmari and Aseel Aldawood: #COVID-19 Misinformation: Saudi Arabia as a Use Case (poster)

This was actually a multi-slide presentation. As Ashwag and Aseel put it in an earlier tweet: ‘Uncertainty fuels coronavirus #rumors and #misinformation. We seek to understand the #Arabic misinformation spread the most in this #COVID pandemic and how misinformation evolve over time.’ Here’s their opener slide and their research questions.

|

|

This was a maxed-methods study, gathering data on misinformation circulating on Twitter, a short survey and government policies and regulations. The second slide shows the misinformation topics investigated: 5G (that it’s bad for you), biological war, health advice, perception of islamophobia, arab immunity (the idea that arabs have immunity to certain diseases simply because they are arabs), pharmaceutical companies and conspiracy theories. Data was gathered using the Twitter API, python tools and manual checking.

|

|

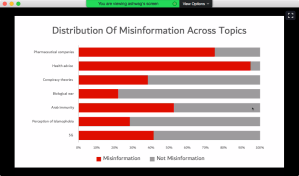

The findings included the distribution of misinformation across topics, and when the spread of various new types of misinformation started. The greatest amount of misinformation is in health advice. Then there is more work to do!

|

|

|

|

Wednesday 10 June

introduction to the day

There was a mixed of excitement about more good things and sadness that this was the last day. There was also a call to think. I said I’d do my thinking when I wrote up my memories of the conference. There was also a poll about whether we like cats or dogs. (48% of the voters were cat-people; 52% were dog-people. I’m neither so I’m not a person.)

|

|

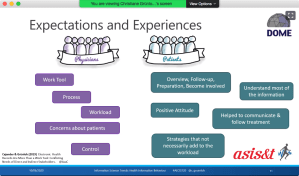

Christiane Grünloh: ‘My Work Tool’ versus ‘My Body, My Data’: Conflicting stakeholder perspectives on digital data access

Christiane began her keynote by telling us a little about her background. She has moved from healthcare to computer science, and moved a lot geographically too. She described some of the changes in healthcare technology: from gruesome tools to high-tech devices, from paper notes to apps. There were also developments in relationships between healthcare professionals from paternalistic styles to shared decision-making. Both patients and doctors can contribute expertise, because patients have expertise in living with their conditions. The examples in the fourth slide are

- how long patients and their doctors spend on self-care (in this case on Parkinson’s disease)

- someone who has developed their own artificial pancreas (I WANT ONE!!!)

- @ePatientDave

|

|

|

|

|

|

Christiane said that, in Sweden, the movement from paper records to e-records was piloted in Uppsala. You can see who has looked at your records. I would want to know when my doctor looked at my records. Was it 30 seconds before a consultation, or several minutes, to allow time for thought? Or is 30 seconds sufficient for a good doctor?

|

|

When the e-records system was piloted (2012, if I heard correctly), some doctors thought it was dangerous for patients to see their records. They saw e-records as their tool, which patients wouldn’t understand. Patients would get upset, question too much or inappropriately, thus increasing doctors’ workloads. Doctors also feared that patients seeing who looked at their records would be effectively surveillance of doctors. See my point above!

But for patients, the e-system was an opportunity to get overviews of their conditions, to prepare and be involved in their treatment. Patients often understood much of their information, often reading the records after seeing their doctors.

|

|

Christiane said that she is interested in why the debate was so heated, not in showing doctors were wrong. She went on to talk about value in design. For example:

- ‘ownership and property’: when the system was first implemented, patients could only see records signed by doctors. But patients wanted to see all data about themselves.

- ‘autonomy’: doctors didn’t want to be forced to change. Some wanted the final say. Of course some patients felt otherwise.

- ‘human well-being’: There was strong feeling by doctors that patients wouldn’t benefit from access to their own records because they would become even more worried. But some patients benefitted from not having to wait to be issues with results. (OMFG, I know that one!)

- ‘trust’ and ‘inter-stakeholder dialogue’. See the different assumptions, and hence the need for effective engagement. It’s not always possible to reach consensus.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

So Christiane’s take-home message was ‘it’s complicated’ because medical records are both a work tool and ‘my body, my data’. However, some concerns about people with mental health issues having access to their records have not materialised. Even better, there is dialogue. And then there was her final moral of this story. This reminded me of Baden-Powell trusting young people to act responsible, and in general they did.

|

|

- it is interesting to see that a shift in information between involved parties was accepted only reluctantly by some. Does a change in information access involve emotional and personal aspects?’

- Christiane mentioned that there are regional differences across Sweden.

- Access to records should be international, so if a Swede (for example) is treated outwith Sweden, those doctors can add information to the Swedish system. ‘my data, my body’ could become ‘my life’.

- Absolutely. For example, you don’t get born, live, die in same place, and hence see the same doctor all your life’. Denmark may be working on such a system. (I have suffered lack of interoperability between NHS England and NHS Scotland!)

- The main problem of access to electronic medical records is that they are not originally developed for patients. Do you think they should be changed?’

- There are both advantages and disadvantages to having jargon.

- There are different systems across the USA (i.e. intra-country differences). Some systems use pen and paper to report coronavirus cases to the CDC. (I say ‘OMFG!)

- And many medical billing systems involve lots of copying and pasting, with attendant mistakes. (This makes me sick. At least as far as medicine is concerned, I’m a state socialist – paying at the point of provision is just BAD!)

- Here is a link to to the English-Language version of ‘Washabich‘, a translation service supported by medial students and doctors.

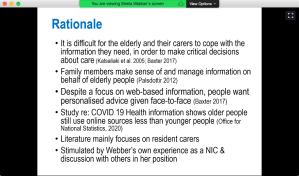

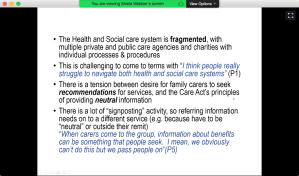

Sheila Webber and Pamela McKinney: The information worlds of non-resident informal carers: stakeholder perceptions

Sheila and Pamela started their presentation by noting that non-resident carers often have to do a lot of travel. Here are the aim and definitions of the work they are reporting on. Then there is the rationale for the work. (Gosh, I’ve lived some of these!) Part of the rational is the need for personalised advice for carers: different age-groups need (in general) different ways to receive information.

Sheila and Pamela’s methods included approaching stakeholders to get an understanding of the background to the care systems, and to obtain evidence of actual problems for non-resident carers.

|

|

|

|

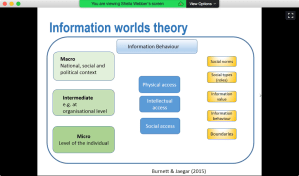

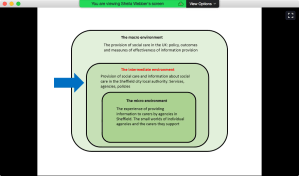

Sheila and Pamela talked about the ‘information worlds’ theory: this includes social contexts and interactions between small worlds and other factors. The overall environment, includes the policy background(s). Note the different levels of devolution – these cause problems. Also, the UK government is trying for a more free-market ethos. (I have no polite words for that!) According to the Care Act 2014 (actual law on legislation.gov.uk, information from the Social Care Institute for Excellence), there should be information for carers but it’s hard to find. Also the demographics of people receiving care are challenging – sometimes old people are seen as a problem.

|

|

|

|

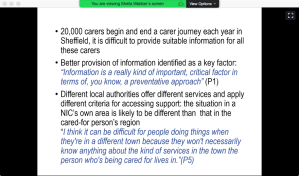

Concerning the intermediate environment (in this case Sheffield city local authority, services agencies, policies etc), there is much signposting. And many people start and finish being carers (presumably for members other families) each year. Also large difference between how different local authorities operate leads to issues.

Concerning the micro-environment, there is less contact into the small worlds of agencies. There are big learning journeys for carers. But there is less access to formal and informal networks. For example, some care support groups may not admit people from outwith their local areas.

|

|

|

|

Sheila and Pamela want to extend their work, for example by collaborating with people in other areas. They talked about the greatest needs of informal carers. (I can’t write about this just now without feeling very emotional.) One issue is finding out what you need to know. During the Q&A session, Sheila and Pamela talked about the ‘fun’ of getting funding (I know this one too!), and the difficulties of investigating ethically. Their experience is that some participants will give a lot of information, but some of that information may break ethical considerations.

Paulina Bressel: Recovery of Eating Disorders on Social Media

We were asked not to tweet Paulina’s slides. Paulina started with her definition of recovery: it’s a process, not an outcome. Paulina did her research on instagram, because it is all about pictures. Step 1 was to search instagram for 4 hashtags. After cleaning her data, Paulina had about 2700 posts. Images were in 4 main groups, including ‘food/drink’ and ‘people’ (mostly smiling, before and after). Paulina also used caption analysis. She found that much personal information is shared, along with tips for other people with eating disorders. Forms of expression were 50% negative, 39% positive, 11% other (I missed what, sorry). There was support and offers of interactions. Analysis of hashtags showed that 47% were sentiment-topic, 38% topic, 15% sentiment. Removal of the ability to add hashtags to Instagram posts caused problems, including hurting the recovery process.

There appeared to be 4 forms of post: eating diaries (with picture of person and/or food, much sensitive personal info); proof that the person posting is now eating; personal experience/transformation; quotes.

Findings included ‘posting all the time didn’t help with my condition’ (That’s my précis, not actual quote.) There are some strange hashtags, e.g. #edfam is used for recovery. (I wonder if it’s because feeling part of a family helps recovery.)

Questions

- Please tell us more about removal of hashtags from instagram.

- shadow-banning, resulting in people not being able to get help from the online community.

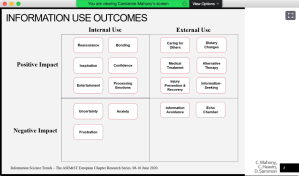

Carolanne Mahony, Ciara Heavin and David Sammon: Health Information Use During Pregnancy

Here is the team that undertook this project. The background was health information seeking. Carolanne noted the move from ‘paternalistic’ to ‘online/ubiquitous’ information-provision, including issues around quality/standards of information available online. Those patients who look for information are seen to be more engaged. But there are problems due to lack of internet access for some. Carolanne positioned the research in terms of Wilson’s general model of information-seeking: information processing and use (Dear me, I have so much reading and learning to do!) focussing on information use outcomes (That interests me too – what do you do with information you have found?)

Concerning the context of the research, for example, women seek health information more. Motherhood is a very significant event. Not all women get ill during pregnancy, but all must make impactful decisions. To do this, they combine information from multiple sources, e.g. on- and off-line.

Concerning methodology, the results being presented now are from the first two interviews with each mother. (The full study also includes interviews up to 12 months after birth.) They had 12 participants. Results indicated that first-time motherhood appears to be high-risk/watershed. The participants had a range of educational levels (high school to PhD). The team used thematic analysis: both deductive (codes derived from literature) and inductive (looking for emergent themes in the data). This was backed up by getting some participants to look at analyses of their own data.

|

|

|

|

Concerning outcomes, i.e. the effects of information-seeking (such as ability to articulate things), Carolanne presented the following results. The slide does not mean that the number of positive outcomes is larger than the number of negative outcomes. (@gemmaducat, @Bruce_Research: note information avoidance!)

Carolanne noted some positive, internal outcomes, e.g. reassurance that ‘I’m not diseased, just feeling sick’); external, e.g. behaviour change. Also cyclical, repeated information-seeking such as looking for more information to help understand information already obtained.

Negative outcomes included uncertainty and anxiety from conflicting information (e.g. from different doctors); the internet enabling unhelpful self-diagnoses. A generally active information-seeker avoided information about maternity. This person had to be helped to read one book at a time. Also, there were echo-chamber effects. Staying off the internet seemed to be a way out for this person who is quoted under the ‘echo chamber’ heading.

|

|

|

|

|

|

The conclusion include cascades leading to reassurance or behaviour-change. Carolanne and colleagues are hypothesising around outcomes of information-seeking being used to inform better information-service designs.

|

|

Closing discussion

This started with a question: do we need to open information first, or teach people information literacy first so they then can use open info. Suggestion that IL is like a muscle: it degrades with lack of use. Aylin Ilhan read my mind: I say both, because we learn by doing.

Talk moved on tohow hashtags and keywords can be changed so they are not deletion-candidates. It was noted that you can change your name to the name of a topic, and suggested that we need to learn how to interact with topics (as opposed to information in general?)

And then, far too soon, it was almost all over. Aylin Ilhan noted that the conference had been a safe room in which we can be constructive. (I hope I’ve not breached that!) But here are the contact details, and a look forward to the future: what will the topics be in future years?

|

|

Pingback: Bruce Ryan and Gemma Webster present on information avoidance and diabetes at Information Science Trends: Health Information Behavior | Hazel Hall

Pingback: My Keynote at Information Science Trends: Health Information Behavior – Christiane Grünloh